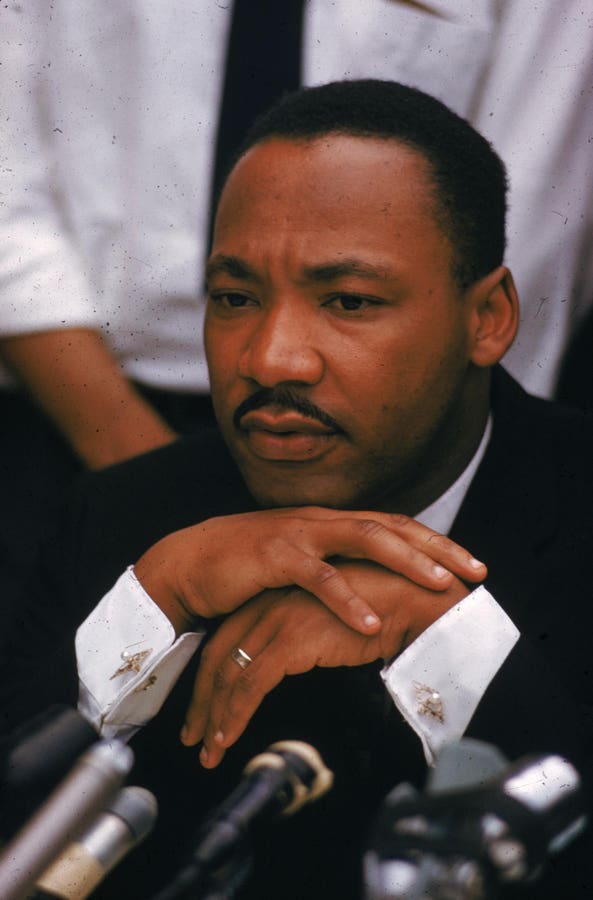

Would health care benefit from more leaders with the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.?

Getty Images

The term ethical erosion is used to describe the “gradual decline of values, beliefs, and truths.”

I first encountered this term in medical school, where it described a loss of empathy and compassion as students grow from their first year of medical school to the end of their training.

New medical students probably have pure values.

They write on their medical school applications that they “want to help people.”

However, by the end of their training, they may prove to be more stubborn and less empathetic than before.

Medical students who once hugged suffering patients may find themselves unable to make eye contact with patients or return phone calls later in their careers.

Simply put, their ethics have changed, or eroded.

This Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I woke up this morning wondering about the erosion of ethics as it pertains to those who work in the business side of health care.

Many people who work on the business side of healthcare (like me) believe that they can make a meaningful contribution to society while living a good life.

But years into our careers and as we integrate into the industry, something changes.

We no longer worry about the reliability of our pablum.

We will stop worrying that the products and services we sell are bankrupting people and society.

We stop worrying about the human impact of our decisions.

Unusual behaviors and practices begin to feel normal.

The reality of keeping your job and keeping your company afloat trumps any previous personal ethics.

By making livelihood part of the equation, the concept of contributing to society is completely destroyed.

“I have a child that I want to send to college.”

“I have a boss who wants results.”

“There are shareholders who are expecting a return.”

When pressed about clearly unpleasant aspects of our business (for example, pricing, access barriers, denial rates, and health care disparities), we revert to the “broken system” narrative.

You might say, “We're just doing the best we can with the incentives and constraints given.”

Or maybe you want to change direction.

Pharmaceutical company executives blame health insurance.

Health insurance executives blamed the doctors.

Doctors are blaming the government.

And so on.

The broken system explanation is easy to accept at face value because it is true.

The system is broken and the cracks are countless.

But descriptions of broken systems are also distracting.

A distraction that often has the intended effect.

It takes away the heat of the person who is under the microscope at that moment.

It helps us avoid intense scrutiny of our own practices and allows us to maintain the status quo.

It reflects the deep, false, numbing helplessness that is the ultimate conclusion of a person's ethical erosion.

Pharmaceutical companies, whose drugs are already expensive, can promise not to raise drug prices above inflation.

But in many cases this is not the case.

Insurance companies that create friction by denying claims that they would eventually approve may approve claims sooner.

But in many cases this is not the case.

Nonprofit health systems that aggressively charge patients with debts they will never recover may promise not to damage the credit of sick and needy patients.

But in many cases this is not the case.

There is no need for regulatory changes to implement these small but meaningful improvements to improve the broken status quo.

There is no change in the regulatory situation.

There are no “major” refurbishments to the system.

There are no significant changes to our financial model or accounting practices.

No, we just need a more robust ethical framework.

A deep belief that not everything has to be the way it is.

A burning desire in your gut to be better.

This raises the question of the ethical erosion of healthcare leadership and what it means to be a healthcare leader at every level of an organization in 2025.

I've been to a lot of meetings and conferences with medical leaders where there's a lot of praise for the issue.

And I feel guilty for being one of those fans.

There is much debate about the root cause. and potential solutions.

But when it comes time to take action, even a small action, we again encounter a deep, false, paralyzing feeling of helplessness.

“I can't do anything.”

“My board won’t let me.”

“Shareholder expectations will not allow that.”

“We need a legal fix.”

Some are true, but many are not.

So we go to more conferences and speak. And we write articles (like this one). And we settle into the idea that we are creating change through dialogue.

Or, more ominously, we remain silent. Oh, we're silent.

A kind of misplaced sense of quiet resignation.

(cricket)

If those who work on the business side of health care more consistently (and loudly) entrenched the simple ethics that drew us to health care in the first place: “We want to contribute to society,” we would rather than as helpless and hopeless objects of the system, which they might have begun to look upon, as promoters of the system.

We may not necessarily believe that change needs to come from outside. Instead, you may begin to believe again that change can come from within.

And we may begin to rebuild the trust we have lost and continue to lose.

We may, like Dr. King, begin to take on the title of “leader” in the classical sense of the word and do what is right even if it interferes with Picayune's interests.

A medical leader who is hopeless, helpless, resigned, and worst of all, silent, just as a doctor who no longer has compassion or compassion for his patients should no longer be a doctor. can no longer feel the change, it is their responsibility and their personal mission should be retired.

Because better, more assertive, more vocal, more independent industry leadership is paramount to delivering much-needed health care to an angry and dissatisfied nation. It is.