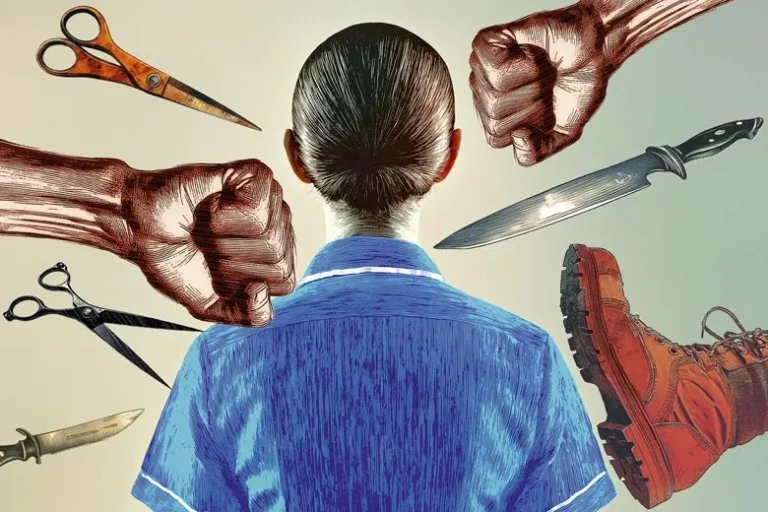

Virtually all nursing and midwifery workers in the UK have experienced physical violence at work, an exclusive Nursing Times survey reveals.

Staff reported being grabbed, punched, bitten, spat at, strangled, headbutted and even stabbed. Some face attacks on a daily basis.

“No one should be attacked at work, especially not when trying to treat people and save lives”

Stuart Tuckwood

The issue is so prevalent that many have been made to think that enduring physical violence is just “part and parcel” of being a nurse or midwife.

Some respondents reported having post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and permanent injuries due to a violent incident in the workplace.

Nursing Times, in partnership with the union Unison, surveyed more than 1,000 nursing and midwifery staff and students during February.

A staggering 93% of respondents said they had experienced physical violence at some point in their nursing or midwifery careers.

A further 87% said that they had witnessed a colleague being attacked.

The problem is driving some people out of the profession, our survey found.

One former healthcare support worker from Scotland, who had a bedpan of urine thrown over her as well as being punched and kicked, said: “I left nursing in January due to violence and aggression at work.

“It is looked upon as being part of the role, rather than changes and improvements being implemented.”

In total, 61% of survey respondents said they had thought about quitting nursing or midwifery due to concerns about violence at their place of work.

Oldham stabbing

On the night of 11 January 2025, nurse Achamma Cherian was stabbed in the acute medical unit of Royal Oldham Hospital.

Ms Cherian was admitted in a serious condition after the attack, understood to have been carried out with a pair of scissors.

She sustained “life-changing” injuries, according to Greater Manchester Police.

At the time of publication, 37-year-old Romon Haque, of Yasmin Gardens in Oldham, remained on remand, charged with her attempted murder.

This attack sent shockwaves through the nursing profession.

One nurse, a bank worker who mostly takes emergency department (ED) shifts, told our survey that the Oldham stabbing had left her in fear.

She said: “I do not feel safe since the incident at Royal Oldham… I do not see myself working in ED or [on] wards any more.”

The attack came as other NHS trusts have reported rises in violence against staff in recent years, leading them to introduce measures, such as body-worn cameras for nurses, and to launch poster campaigns to try and tackle the problem.

Last month, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust announced that it was equipping senior nurses with bodycams on certain wards that had become violence “hotspots”.

Violence is also negatively impacting workforce capacity in other ways, with 33% of respondents reporting that they had needed time off work to recover from a violent incident and 22% saying violence had forced them to change roles in healthcare.

A registered nurse in Scotland said: “I had PTSD following being attacked and required trauma therapy. I have permanent injuries due to this and [had] to be redeployed.”

Many respondents cited a “victim blaming” attitude towards violence in healthcare.

“It’s always the staff member’s fault for upsetting the violent person,” said a community nurse in England.

The survey found that violence was a particular issue in mental health nursing.

Of the 263 respondents who worked in NHS mental health services, 99% said they had experienced physical violence.

Meanwhile, “perpetrator having mental health problems” was cited as the most common aggravating factor in the incidents of violence that respondents had experienced, followed by “perpetrator being cognitively impaired”.

One student mental health nurse in England said she faced attacks several times a week including being “thrown over [a] tea trolley, choked and pinned against a wall”.

A trainee nursing associate working in a mental health hospital in England said they had been “stabbed in the neck and stomach, punched and [had my] teeth knocked out”.

Lack of police action was highlighted as a concern by many.

One mental health nurse (RMN) said: “Police often do not take these incidents seriously and it is expected that [violence] is [part of] an RMN’s role.”

The same nurse went on to say that, in almost every case of assault against her, it was due to “patients not being permitted to smoke when they wish”.

No-smoking policies were also cited by others as an aggravating factor in nursing staff being attacked.

“District nurses are often forgotten about and are one of the most at-risk workers”

Survey respondent

The challenges of responding to violence from patients with cognitive issues, such as dementia, were also flagged.

A community nurse in England said staff did not report such attacks because they “consider [those patients’] aggression/violence as beyond their control”.

A social care nurse in England, working with patients with dementia, said violence was seen as coming “with the territory”.

The systemic pressures facing health and social care appear to be contributing to the problem.

Of respondents who had experienced violence at work, 44% cited staff shortages as an aggravating factor.

A hospital nurse in Wales said: “Poor staffing levels inflame the situation.”

More than a quarter (27%) said that patients being treated in inappropriate settings – such as hospital corridors or acute hospitals when mental health care was needed – was an aggravating factor, and 19% said the same about patient waiting times.

Lone working was also listed as an aggravating factor by 10% of those who had been attacked.

A community nurse in England said: “District nurses are often forgotten about and are one of the most at-risk workers.”

The survey also asked respondents whether they were targeted because of a protected characteristic. The most common answer was “no”, but 15% of those who had faced violence said they felt attacked because of their race and 13% said the same about their sex.

Positively, 93% of nursing and midwifery staff who experienced violence at work said they reported at least one of the incidents to their employer.

However, only a third felt supported, while 53% felt unsupported.

Concerningly, three-quarters of all respondents said they did not feel safe from violence at work. Among them was a hospital nurse in Northern Ireland who reported having a gun pulled on her while triaging a patient.

Employers have taken steps to try to curb violence, such as rolling out staff training, putting up posters or other campaign materials, and introducing violence prevention and reduction risk assessments.

Despite this, 69% of respondents said they felt their employer failed to take the issue of violence against nurses and midwives seriously enough.

Unison national nursing officer Stuart Tuckwood described the findings as “truly shocking”.

He said: “No one should be attacked at work, especially not when trying to treat people and save lives.”

Mr Tuckwood added that employers had to do “far more” to address the issue or risk having more nurses quit.

“And that would make the dire staffing situation significantly worse,” he warned.

Zoya Madar

Attacks are daily occurrences for mental health nurses, Zoya Madar said.

One patient left her with a dislocated shoulder, while other incidents in her career saw her punched, kicked and spat at.

Zoya Madar

In a particularly bad incident on an inpatient ward, Ms Madar was punched in the stomach so hard she fell to the floor, hitting her head as she went down.

Other nurse colleagues have been strangled or had objects thrown at them, she said.

The frequency, and severity, of attacks has sometimes left her fearing for her life at work: “I have felt… so unsafe that you are questioning if you’re going to leave the situation in one piece. The level of violence, honestly, is quite spectacular.”

Violence is less common in her current role as a senior primary care mental health nurse at Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust – but the challenges facing her specialty remain, she said.

“It shouldn’t be a part of anyone’s job to be attacked,” she added.

Ms Madar said lacklustre responses from authorities had made her question whether she should quit nursing.

She claimed a police officer once told her to “develop more resilience”, after she reported an attack.

“These kinds of attitudes make me think about stepping away from a job I absolutely love,” she said.

She advocated for some nursing staff to wear cameras, having seen a marked reduction in violence after they were introduced at an urgent care unit at which she used to work.

Josh Vella

Josh Vella, a nursing student at the University of Chester, has been punched, kicked and even attacked with sharp objects during placements on adult wards.

One patient grabbed a pair of, thankfully blunt, scissors and “made a good attempt” at stabbing his arm.

Josh Vella

He escaped the incident with only minor injuries, although he was left shaken.

“Once the adrenaline kicks in, you go: ‘Well, I’m fine,’ and then you realise you’re actually not,” he said.

“Thankfully… I was straight into [my assessor’s] office for a sit down [and] to check if they needed to send me off.”

Mr Vella felt there was a common sentiment that violence was “part of the job”.

Staff shortages, he said, contribute to attacks against nurses.

He recalled an incident triggered by a patient’s frustration about slow care; on this occasion, 30 patients were being managed by himself, one registered nurse and two healthcare assistants (HCAs).

Mr Vella said he once considered quitting his course after he saw a patient hit an HCA so hard her jaw was broken.

Fiona Stevenson

A headbutt from a patient with dementia last year left Lancashire and South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust nurse Fiona Stevenson with a broken nose.

Fiona Stevenson

Describing another incident involving a patient, who also had dementia, she said: “We were having a reasonably good conversation, and they picked me up out of my chair and threw me across the room.”

She criticised the fact that there is a lack of post-incident support for nurses.

Ms Stevenson, who has worked in both dementia and mental health care, said there was a generational divide between veteran nurses and more recent registrants, like herself, who first entered the register five years ago.

“[They] say it’s part of the job,” she said.

“We who have recently qualified do not accept it… we expect a pathway of [it] being dealt with, [of us] being listened to. But we have come across a lot of resistance.”

Ms Stevenson said poor staffing and patients being placed on the wrong wards for their needs was partly to blame for attacks, although de-escalation training had helped.

However, she said she would object to measures such as body-worn cameras for nurses, fearing it could compromise the relationship between staff and patients.

Read more on the topic of violence against nurses