An MRI can cost anywhere from $300 to $3,000 depending on where you get it done. A colonoscopy can cost anywhere from $1,000 to $10,000.

Economists have offered the analogy of medical cost roulette in urging Congress to require hospitals and health care providers to provide medical costs up front.

Supporters of the Health Care Transparency Act 2.0 are hoping that lobbying from an influential group of economists will convince lawmakers to move forward with a Senate bill introduced in December by Sen. Mike Braun, R-Indiana. The bill, co-sponsored by 11 Democratic and Republican senators and Vermont independent Sen. Bernie Sanders, has failed to get out of committee. Brown’s “number one priority is to get this bill out of committee and to get it to the floor for a vote,” said Alison Dong, Brown’s deputy communications director.

In a letter to senators on Monday, 32 economists, academics and business leaders said price transparency would save up to $1 trillion in wasteful health care spending each year and help middle-class workers “whose paychecks are being eaten up by rising health care costs.”

Economists argued that cost savings for patients would boost the economy and provide savings to workers whose wages have stagnated because their employers are footing the bill for soaring health care costs.

Vivian Ho, an economist at Rice University who signed the letter, said the bill would give employers and consumers a price-comparison tool to shop around for better health care prices. By allowing consumers to choose lower-cost hospitals, labs and same-day surgery centers, it would reduce health care spending and, in theory, make health insurance cheaper, she said.

“So much of America’s middle-class wealth is locked up in hospital cash reserves,” said Ho, a professor of health economics at Rice University’s Baker Institute.

What effect will the Price Transparency Bill have?

Hospitals are already required to disclose some pricing information. Federal rules that took effect in 2021 require hospitals to publish cash prices and fees negotiated with health insurers for a wide range of procedures in a computer-readable format that makes the information analyzable. The rules also require hospitals to publish quotes for at least 300 services so consumers can compare prices.

But critics say current federal rules have too many loopholes: Price-estimating tools don’t show actual prices, and machine-readable files are often littered with incomplete, inaccurate or broken data. Fifteen hospitals have been fined for not publishing prices, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The Brown bill would require health care providers to submit computer files of all charges and cash prices negotiated with hospitals, health plans, laboratories, imaging centers and same-day surgery centers. These providers would have to provide actual prices, not estimated prices. Federal regulators would determine the format for reporting the data.

Healthcare providers must certify that all prices are accurate and complete or face fines. Penalties are based on the size of the hospital. For example, a 500-bed hospital could be fined up to $10 million if it doesn’t comply.

Hospitals said they are concerned the bill would eliminate price quotes, and that forcing facilities to list actual prices could confuse consumers.

In a letter to the Senate committee at a July hearing, the American Hospital Association said hospitals had warned that doing away with price quotes was a bad idea.

The hospitals said eliminating price quotes would “remove a consumer-friendly research tool and unfairly penalize hospitals that have spent millions of dollars to comply with regulations.”

The hospital added that list prices “can be confusing to consumers and do not reflect the various policies insurers apply to determine the final price of a service.”

But employer groups say price is more important than quotes: Employers who offer health insurance to working-age Americans need to know the actual price when they sponsor their employees for coverage.

James Gelfand, president and CEO of the ERISA Industry Committee, an employers’ trade group, said price transparency will help employers make smart choices when selecting benefits for their employees and their families.

“Transparency is critical to controlling health care costs for employers and workers,” Gelfand said. “Senator Brown’s bill is the strongest health care cost transparency bill because it requires disclosure of actual prices, not estimated prices.”

Other experts say consumers feel more comfortable buying medical products if they know the price. Ge Bai, a professor of accounting and health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University, said more consumer-friendly medical supply sellers, such as GoodRx, entrepreneur Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs and Amazon, provide clear pricing information to consumers.

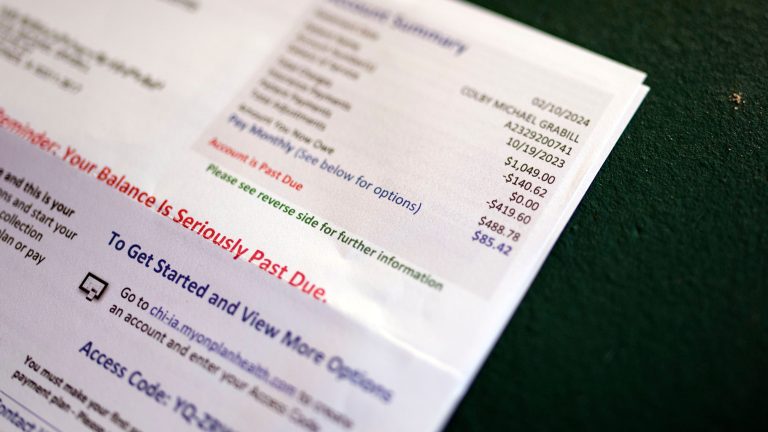

She said greater price transparency would allow more consumers to compare prices at different hospitals and clinics before seeking treatment. With 100 million Americans carrying medical debt, such a tool could help consumers shop around for cheaper prices and avoid high bills.

“Consumers want more control over their health care costs, and price transparency will help them,” Bai said.

Rising medical costs put pressure on workers’ wages

Rising health care costs have forced employers and consumers to spend more on health care, the economists said, citing a 2023 KFF report that noted the cost of a typical family health insurance plan is about $24,000 a year, up 50% from a decade ago.

With employers paying most of the cost of health insurance, companies have less funds to hire more employees or give raises, Ho said.

Employers often don’t realize that rising health care costs will translate into lower pay, a trade-off companies make when calculating total compensation.

A Willis Towers Watson study found that 40% of the increase in compensation that low-wage workers have earned since 2000 has gone towards health insurance premiums, the economists said in the letter.

“Workers don’t understand this at all,” said Ho. “They only see their take-home pay and don’t always think about how much is going into insurance premiums.”