Demographic characteristics of participants

Of the 104 participants recruited in this study, 30.8% were from control areas, 63.4% were from endemic areas, and 5.8% were from non-endemic areas. The overall mean age of respondents was 36.3 ± 11.3 years. The majority of respondents were male (88.5%). Educational background varied among respondents. There were no illiterate participants in this study. Almost half of the participants (n = 53, 51%) had a degree in a related profession. In endemic areas, most participants (n = 40, 60.6%) were engaged in laboratory work, whereas the majority of health facility owners/managers (n = 21, 65.6%) were in control areas. (Table 2)). The p-value showed that there were statistically significant differences in education level (p = 0.002) and health center role (p = 0.003) between regions.

A total of 26 providers participated in the FGD. Of these, 88.5% were male, and 50.0% were clinical laboratory technicians engaged in diagnostic work (Table 3).

Characteristics of health facilities

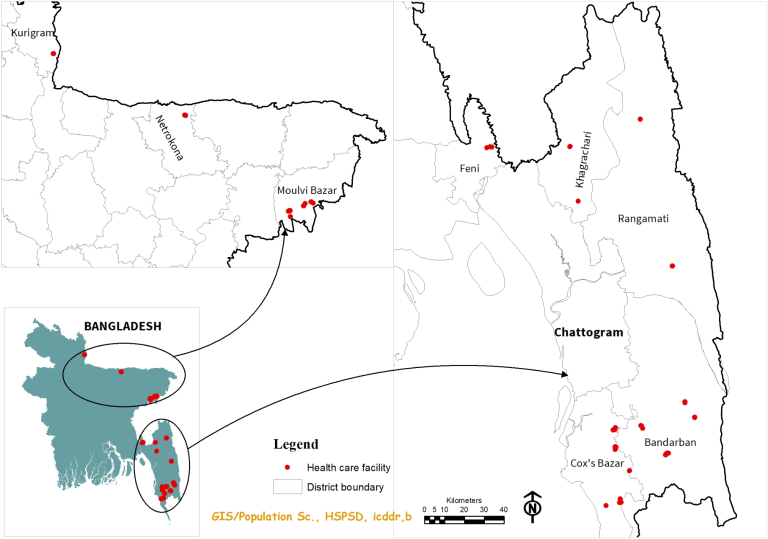

Five types of commercial private healthcare facilities were listed and mapped. More than half of these were consulting and diagnostic centers (54.8%), followed by private clinics (18.3%) and drug stores (13.5%). Private commercial health facilities were located close to the corresponding Upazila Health Complex (UHC) but at a distance from the nearest district hospital. Health facilities in non-endemic areas were significantly closer to UHC and district hospitals than those in control and endemic areas (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Availability of malaria diagnostic and treatment services

In total, 80.8% of the listed facilities provided malaria testing services. However, the comparison showed that the availability of testing services, both rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and microscopy, was highest in endemic areas (65.0%), followed by non-endemic areas (50%) and control areas. (33.3%) However, this difference was not considered statistically significant. Of the 84 facilities, 66.7% in both control and endemic areas and 100% in nonendemic areas utilized RDT as their primary testing method. Of these, 66.7% in both control and non-endemic areas used only WHO prequalified RDTs, whereas this proportion was only 32.5% in endemic areas. RDT costs vary by region. In control and endemic areas, the average cost per RDT was 150 BDT (US$1.5) and 250 BDT (US$2.5), respectively. However, in non-endemic areas, the cost was significantly higher at 600 BDT (6 USD), and this difference was statistically significant (Table 5).

However, during the FGD, it was noted that most participants emphasized blood slide technique as the preferred approach for diagnosing malaria parasites. The rate of microscopic diagnosis varies depending on weather conditions and seasonal fluctuations, and can range from 10 to 15 cases, or even more in some cases.

“We have noticed that the practice of diagnostic reporting for malaria is successful because in Slemongol it is either positive or negative. In some cases the malaria parasite is not found, and in other cases it is positive; It may be missed. Therefore, the malaria blood slide test report should include a statement of “found'' or “not found.'' ” (Participant: FGD Slemongal, male, 28 years old)

Drug store owners and dispensers utilize RDT kits from a variety of sources, including local and third-party suppliers. In some cases, private health centers may receive RDT kits from the Bangladesh Rural Development Commission (BRAC) consortium NGOs. Fees for microscopy and RDT vary based on management decisions, service capabilities, and reputation of the private facility. In our study area, the cost of RDT ranges from 60 BDT (0.6 USD) to 200 BDT (2 USD), whereas blood slide microscopy is relatively cheaper, costing only 40 BDT (< 0.5 USD) to 70/ It's 80. BDT for patients (0.7/0.8 USD).

Regarding malaria treatment services, the opposite scenario was observed compared to malaria testing services, with only 18.3% of service providers offering malaria treatment services. Despite these regulations, health facilities in the three regions did not even begin treatment for malaria until test results were available. Almost all health facilities selected in this study (n = 100, 96.1%) did not provide the necessary treatment for patients with severe malaria.

“Serological testing is performed in a private laboratory along with the RDT, but does not provide treatment. If malaria is suspected in a patient who has a fever with cold-like cough symptoms, a referral from the resident medical officer is recommended. We conducted malaria tests only on patients who received the malaria test. Our health center has a doctor on duty 24 hours a day, so we can treat them if anti-malarial drugs are available at the health center.” (Participant: FGD) Arikadam, female, 23 years old)

Additionally, similar to RDT, local wholesalers were the main source of antimalarial drugs. Only four treatment providers claimed to treat patients with severe malaria. However, only two of them followed a specific treatment protocol (Table 6).

Barriers to efficient diagnosis and case management of malaria

During the FGD, participants mentioned several practical reasons that hinder efficient malaria diagnosis. Limited equipment, inconsistent power, and poor quality rapid diagnostic tests exacerbate this problem. One participant expressed concern about false positives from these tests and emphasized the need for better solutions.

“I believed that the RDTs used in local diagnostic centers and clinics were of poor quality and could not accurately diagnose malaria.Last year, there was a case in which malaria was identified by RDT, but I When we examined the blood slides using a microscope in our laboratory, we found no malaria parasites.'' (Participant: FGD Slemongol, male, 48 years old)

Another major challenge in implementing microscopic malaria diagnosis in commercial private health facilities was the lack of sufficient staff. Clinical laboratory technicians are required to perform a variety of serological and hematological tests on a daily basis, while also being under pressure to quickly submit malaria reports for commercial purposes due to early requests from attending physicians and hospital management. was also exposed. This insufficient staffing was a major barrier to maintaining the quality of malaria diagnosis.

Participants also stated that testing and interpreting malaria tests was not easy for people who had just completed a bachelor's degree in medical technology. This may also be due to the curricula and textbooks taught that placed less emphasis on malaria and lacked laboratory training sessions. Additionally, most newcomers were unable to understand or effectively perform blood slide tests to identify malaria parasites, they said. A FGD respondent said:

“Laboratory technicians have developed their knowledge by performing malaria tests in the laboratory. This training will focus on Plasmodium identification strategies to fill the knowledge gap.” (Participant: FGD) Arikadam, male, 45 years old)

Without proper training, private sector laboratory technicians and nurses had very limited or no knowledge of malaria case management.

“The training and monthly medical camps planned for malaria diagnosis and treatment during the campaign will be beneficial for people living in remote areas of the Tea Garden region.” (Participant: FGD Slemongol) , male, 45 years old)

Service providers during FGDs said they usually refer patients to government health centers for treatment. Nevertheless, in some cases, a small number of individuals selling medicines offered treatment for mild or uncomplicated cases, provided they had antimalarials in their stores.

Malaria case reporting and referral

The median number of febrile patients who experienced fever in the past 2 months was higher in control areas than in endemic and non-endemic areas. However, the median number of fever patients tested for malaria was relatively low in all regions. In non-endemic areas, not a single patient with fever has been tested for malaria in the past two months. Of the 23 facilities that claimed to have been diagnosed with malaria in the past two months, only 4 of the 23 facilities reported this to NMEP. The main reasons for not reporting to NMEP include lack of knowledge and uncertainty regarding reporting procedures. Malaria patients were mainly referred to UHC and NGO laboratories/health workers, with limited referrals to local hospitals (Table 7).

During the FDG, participants preferred to report and refer malaria cases to the government. We propose that health facilities and NGOs working under the umbrella of NMEP establish regular case reporting and incorporate the national database and system of the NMEP platform. Nominations arose from the participants of Chakaria FGD.

“The Office of the Civil Surgeon should play a leading role in monitoring malaria cases reported to NMEP in a timely manner. It was proposed that instructions be provided through paper-based reporting. However, A monthly, online-based reporting format is convenient for the private commercial sector, clinics, and diagnostic centers. Additionally, continuous monitoring by NMEP is required to ensure honest reporting and submission. (Participant: FGD Chakaria, male)

Relationship with NMEP

Collaboration between health facilities and NMEP was found to be limited, with only a few facilities (6.7%) reporting commitment to the program. Reporting of positive malaria results to tertiary facilities varied by region, with higher reporting rates in endemic regions (56.1%) than control regions (21.9%), while there were no reports in non-endemic regions during the study period. Mobile phones were the main reporting method (78.4%) in both control and endemic areas.

Most healthcare facilities (62.9%) expressed an intention to collaborate with NMEP. However, concerns about additional workload (61.1%) were the main reason for reluctance to such collaboration. One-third of the participants preferred to receive training through the NMEP training module. Furthermore, only a small proportion of respondents (12.5%) had received malaria training in the past 3 years (Supplementary Table 1).

Private, for-profit medical centers are primarily driven by business interests and seek to profit from each patient who visits, including those with suspected malaria. In addition, pharmaceutical distributors expect to receive an honorarium as a service fee when RDTs are supplied to distributors. FGD participants expressed concerns about working with NMEP on eradication efforts and the need to introduce a service charge to compensate for low pay and often stressful and long working hours. emphasized. Therefore, it may be unrealistic to expect private, for-profit facilities to provide free services. Introducing additional service charges could increase the willingness and dedication to manage malaria cases in line with the business interests of these facilities. FGD participants from Arika Dam expressed the following options:

“From this discussion, in the management of malaria patients, we are responsible for several types of tasks, such as diagnosis through RDT, provision of medicines, storage of patient medical history, and storage of contact information for each patient. But we do not directly benefit from these efforts, so we need to allocate some financial support to participate in this eradication plan.'' (Participant: FGD Arikadam) (Male, 41 years old)