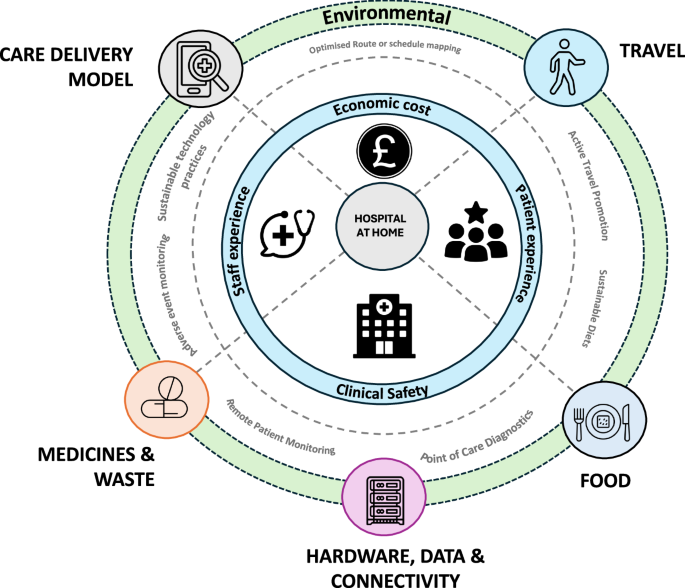

Estimates suggest that if the global healthcare sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases8. Healthcare therefore plays a key role in mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change. As a result, the NHS in England, which accounts for around 4% of England’s total carbon emissions, has set itself the ambitious goal of becoming the world’s first net-zero healthcare system by 20459,10,11,12. In this section, we highlight some key aspects that require attention in the pursuit of achieving a more environmentally sustainable HaH (Figure 2).

We explore key environmental considerations for Healthcare at Home (HaH), including care delivery models, transportation, food, hardware, data, connectivity, medicines, and waste. Portions of this illustration feature icons taken from the Noun Project, all licensed under the CC BY 3.0 license.

trip

In England, travel by patients, visitors, staff and suppliers to NHS facilities accounts for around 3.5% of all road trips, which accounts for around 14% of the total emissions of the health system11,13. This not only increases traffic but also has negative impacts on air quality, resulting in significant environmental and health costs. Indeed, studies suggest that air pollution caused by NHS-related travel is linked to increased mortality and societal costs of over £345 million14,15. Promoting active travel by cycling and walking could have synergistic benefits for health and the environment.

In addition to electrifying transport, technology can also aid in route planning for staff travel16 and patient support programs to promote self-management and community engagement17,18. Decentralized care offers further opportunities to reduce emissions, such as providing multidisciplinary consultations and co-locating providers and allied health professionals to minimise patient travel. However, the broader paradigm shift to bring care closer to home will require detailed exploration of the impacts of these changes, including challenges such as equity of access and cost.

Care Delivery Model

The environmental impact of health and social care has significant implications for the places and environments where care is delivered19. For example, the carbon footprint of an average GP consultation is 6 kg CO2e (rising to 18 kg CO2e if a prescription is present), while the carbon footprint associated with an elective hospital admission is 708 kg CO2e19. Technology-enabled models of care, such as the use of telehealth, can increase capacity and support patients in a more environmentally sustainable way. However, barriers remain in quantifying the environmental footprint of individual patient care pathways, which can make comparison of alternative models difficult. There is an opportunity to move away from carbon impact estimates towards greater use of more standardized, objective methods, calculations, and real-world life cycle assessments.

Pharmaceuticals and waste

Medicines place a huge burden on the environment, accounting for 25% of all emissions within the NHS.11 It is estimated that between a third and half of patients receiving long-term care outside hospital do not take their medicines correctly, costing Europe €125 billion and 200,000 premature deaths each year.20,21,22 There are therefore opportunities to investigate ways to improve patient adherence, monitoring for adverse events, decentralized clinical trials and the use of technology to reuse and recycle unused medicines where appropriate.

Waste is another challenge and opportunity for community care. The NHS in England alone generates around 156,000 tonnes of healthcare waste each year12. Providing more care for communities and greater use of HaH will require a recalibration and consideration of best practices around when, where and how waste is collected. This change could also be an opportunity to embrace technology and innovation to explore how to reduce inefficiencies and embrace circularity principles.

Hardware, Data and Infrastructure

While digital innovation and diagnostics offer many opportunities to improve healthcare, technology-enabled care itself has an inherent and often significant environmental footprint23,24. Increasing reliance on digital and data to enable the transition from hospital-based care to HaH will therefore require a reconsideration of the potential negative impacts of digital infrastructure, data and hardware, and mitigation measures. This is particularly important with regard to technologies that enable remote patient monitoring, point-of-care diagnostics and the interoperability required to interface with existing electronic health record systems and infrastructure. Closer consideration will also be needed regarding how devices used for remote patient monitoring are procured (including their carbon content), deployed and reused. In particular, research has shown that there is a high proportion of “dormant” devices in consumer technology, with devices no longer in use hindering recycling and a circular economy for wearable and mobile devices25,26,27. Other factors to consider include the material or carbon footprint of the hardware used, which includes materials used, durability, energy charging capacity and efficiency26. Additionally, there is an opportunity to consider reduce, reuse and recycle principles within diagnostics, hardware and technology, such as considering the minimum resolution required for scans, images and videos to avoid unnecessary data processing and storage.

food

Although traditionally not considered within the remit of HaH services, social determinants of health, including diet, have a major impact on our health, economy and environment. Here, we propose to include diet in the discussion as a key concern going forward. In 2021, it is estimated that the NHS spent £6.5 billion on obesity-related ill health28. At the same time, the NHS in England spends £633 million on 140 million inpatient meals per year29. It also emits an estimated 1,543 kilotonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions per year, which represents about 6% of the total NHS emissions29,30. An opportunity therefore exists to mitigate this environmental impact while promoting public health at the same time. One solution that has already been proposed is to encourage the adoption of healthier diets, including seasonal fruits and vegetables, pulses and legumes, and alternative protein sources with a lower environmental footprint31. However, ensuring this is equitable access involves many considerations and complexities, including cost, practicality of implementation and acceptability. Overall, shifting home-based care to the community and hospital will require close consideration, engagement and evaluation of the role of food interacting with existing delivery and funding models. This may include where innovation and technology can potentially support (e.g. personalised nutrition advice, meal planning, remote monitoring and delivery services).