Long-term services and supports (LTSS) encompass the broad range of paid and unpaid medical and personal care services that assist with activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals, managing medication, and housekeeping). They are provided to people who need such services because of aging, chronic illness, or disability, and include services such as nursing facility care, adult daycare programs, home health aide services, personal care services, transportation, and supported employment. These services may be provided over a period of several weeks, months, or years, depending on an individual’s health care coverage and level of need.

More than 6 million people use paid long-term services and supports (LTSS) delivered in home and community settings and more than 2 million people use LTSS delivered in institutional settings, according to CBO estimates. An unknown, but likely larger number of people, use unpaid LTSS provided by family, friends, or neighbors. Virtually all people ages 65 and older and about 8 million people under age 65 with disabilities have Medicare, but Medicare generally does not cover LTSS. (See Box 1 for more information.) Most people who use paid LTSS either pay for it directly or have services covered under Medicaid. State Medicaid programs must cover LTSS provided in nursing homes, while coverage for most home and community-based services (HCBS) is optional. Eligibility for Medicaid LTSS is complex and varies widely by state. To qualify for coverage of LTSS under Medicaid, people must meet state-specific eligibility requirements regarding their levels of income, wealth, and functional limitations.

In addition to long-standing questions about the costs, affordability, and coverage of LTSS, there are also longstanding challenges finding enough workers to provide LTSS for people who need such services, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated those issues considerably. As of January 2024, employment levels in most LTSS settings remained 4% below pre-pandemic levels. The Biden Administration finalized two rules intended to address the LTSS workforce and access to services. To address workforce shortages in nursing facilities, the Administration finalized a rule that would create new staffing requirements in nursing facilities, require state Medicaid agencies to report on the percent of Medicaid payments for institutional long-term services and supports that are spent on compensation for direct care workers and support staff, and provide funding for individuals to enter careers in nursing facilities. The Administration also finalized a rule aimed at ensuring access to Medicaid services, which included several provisions aimed specifically at LTSS provided in people’s homes and the community, including requiring states to spend least 80% of total payments for certain HCBS on compensation for direct care workers. In addition to federal action, many states have adopted payment rate increases for nursing facilities and HCBS providers with the goal of boosting staffing levels, as reported to KFF in a 2023 survey.

1. Long-term services and supports are extremely expensive and not generally covered by Medicare or health insurance.

The prices of health care services are quite high, but a greater percentage of people who use LTSS pay full price for that care when compared to other health care services. The difference between LTSS and other health care spending stems from the fact that private health insurance generally does not cover ongoing LTSS and Medicare’s coverage is limited to specific circumstances (see Box 1). The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that an average American turning 65 today will incur $120,900 in future LTSS costs, with families paying for over one-third of that themselves. This is higher than the 17% of overall LTSS expenses paid for out-of-pocket shown in Figure 2 because overall LTSS expenses include expenses for those who are under 65.

In 2023, the median annual costs of care in the U.S. were $62,400 for full-time homemaker services (people who help with instrumental activities of daily living such as preparing meals and doing laundry), $68,640 for full-time home health aide care, $116,800 for a private room in a nursing home, and $288,288 for round-the-clock home health aide services, all of which far exceed the median income for Medicare beneficiaries (about $36,000 in 2023, Figure 1). Such costs would also quickly exhaust the median savings for Medicare beneficiaries in 2023 ($103,800). Although nursing facility costs may be higher than the costs of some home-based services, nursing facility costs include round-the-clock monitoring and the costs of room and board. For people living in residential settings, the costs of maintaining a home such as rent, a mortgage, and other household expenses are paid separately from the costs of LTSS. The average costs of an assisted living facility ($64,200) only include the costs of room and board, so any LTSS expenses would be added to that total. Many people may use multiple services simultaneously, so their total annual costs may be like those of nursing facility or round-the-clock care.

Box 1: Does Medicare Cover LTSS?

Medicare is the federal health insurance program established in 1965 for people ages 65 or older, regardless of income or medical history, and later expanded to cover people under age 65 with long-term disabilities. Today, Medicare provides health insurance coverage to 66 million people, including 58 million people age 65 or older and 8 million people under age 65. Medicare covers a comprehensive set of health care services, including hospitalizations, physician visits, and prescription drugs.

Medicare does not generally cover long-term care services but does cover up to 100 days of skilled nursing facility care following a qualifying hospital stay and covers home health services for people who need part-time or intermittent skilled services. As part of the home health benefit, Medicare covers nursing, physical, speech and occupational therapy, and also covers home health aide services, but only for people getting skilled nursing care at the same time, and not on a full-time basis. KFF polling shows that four in ten adults overall incorrectly believe that Medicare is the primary source of insurance coverage for low-income people who need nursing facility care or home care over a long period of time.

Medicare covers skilled nursing care for up to 100 days each benefit period in a certified SNF after a qualifying hospitalization.

For those who are ”homebound,” Medicare will pay for nurses and therapists to provide services in the home if the beneficiary needs skilled services. Being homebound does not mean that Medicare beneficiaries are unable to leave their homes, but rather that leaving the home is difficult or not recommended because of illness or injury; or that one is normally unable to leave the home because doing so is a major effort. Under those circumstances, Medicare will cover home health care services provided through a certified home health agency for up to 28 hours a week, with more intense care permissible for a short time period when determined necessary by a doctor.

Historically, home health and skilled nursing services had been denied in Medicare for beneficiaries when the purpose was for maintenance rather than for rehabilitation, but the Jimmo settlement in 2013 clarified that coverage of skilled nursing and home health care in Medicare was contingent upon beneficiaries demonstrating a need for skilled care rather than a requirement that beneficiaries show potential for their condition to improve.

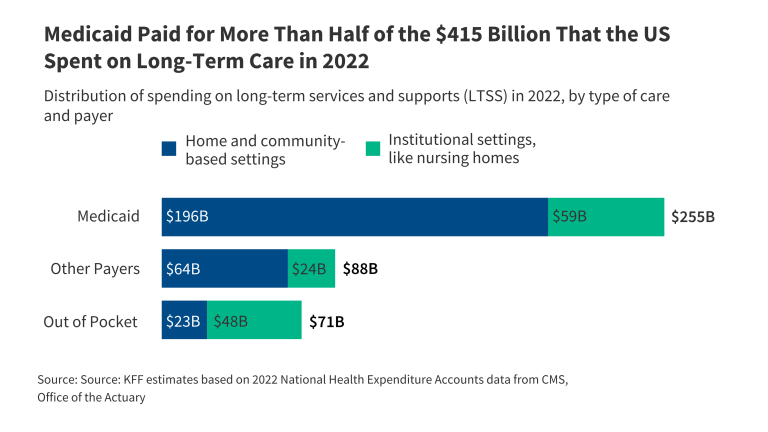

2. Medicaid paid for more than half of the $415 billion that the US spent on LTSS in 2022, most of which went to home and community-based services.

In 2022, the U.S. spent over $400 billion on LTSS, most of which went to home and community-based services (HCBS), based on KFF estimates of annual National Health Expenditure (NHE) data. Spending on home and community-based services was $284 billion and the remaining $131 billion was spent on institutional LTSS such as nursing facility care (Figure 2). Medicaid paid more than half (61%) of total US spending on all LTSS, followed by out-of-pocket spending (17%), and other public and private payers paid the remaining 21%. (See Box 2 for a description of what services and payers are included and excluded from LTSS spending in the KFF analysis.)

Box 2: How does KFF define LTSS in the NHE data?

Unlike other sources of information on health care spending, the NHE use an accounting structure that captures all expenditures of health care goods and services and investment in the health care sector. Expenditures are classified into high-level service categories and by source of payment. Data sources include federal administrative data, household and individual surveys, surveys of businesses, and economic data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

KFF defines LTSS to include spending for residential care facilities, nursing homes, home health services and HCBS waivers. HCBS waivers may include a wide range of services such as adult daycare, home health, personal care, transportation, and supported employment. Under the NHE methodology, assisted living services are in both HCBS and institutional categories. Payments made to the assisted living facilities themselves are counted as institutional care unless they are paid for by Medicaid, in which case they are considered HCBS. For services such as home health and personal care that are provided to people in assisted living facilities, they would be considered institutional care if provided through the facility, but HCBS if provided through another provider such as an affiliated home health agency.

KFF’s definition of LTSS includes spending from any of the following sources: Medicaid, individuals, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, the Indian Health Services, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Veterans Health Administration, general assistance, other federal programs, other state and local programs, school health, and other private revenues. Medicaid expenditures may include some home health spending that is rehabilitative and not LTSS.

KFF excludes spending from certain payers. Within the excluded spending is $94 billion in Medicare spending, most of which is post-acute care, but some of which is home health spending that might be considered LTSS (see Box 1). KFF also excludes spending from private insurance because much of those expenditures are for rehabilitation and not LTSS. In most cases, private long-term care insurance reimburses people for the expenses they pay out-of-pocket and would be classified as out-of-pocket spending in the NHE data. KFF’s approach would exclude private long-term care spending in cases where private plans make payments directly to an organization, which is most likely for individuals using nursing facility care. Such situations are expected to be uncommon given few individuals receive benefits from long-term care insurance in any given year (see Figure 6).

3. Among the 6 million people who use Medicaid LTSS in the U.S., most are using HCBS and over half are under 65.

In 2021, three-quarters of the 5.7 million people who used Medicaid LTSS were receiving HCBS, but this ranged from 49% in Florida to 98% in Oregon (Figure 3.1). The larger share of people receiving care in the community as opposed to in an institution reflects initiatives to make home and community-based care more widely available in recent years and to remove what has been referred to as the “institutional bias” in Medicaid. Analyses of Medicaid spending on LTSS show that the percentage of LTSS spending that pays for HCBS has increased from only 10% in 1988 to 62% in 2020. While the number of people using Medicaid HCBS exceeds the number who use institutional care nationally, Florida still provides services to more people exclusively in nursing facilities and other institutional settings than in home and community-based settings.

Over half (57%) of Medicaid enrollees who use LTSS are under 65: Among Medicaid enrollees who use HCBS, 63% are under age 65 compared with 30% of those who use institutional LTSS (Figure 3.2). LTSS are commonly associated with people ages 65 and older, but many younger enrollees use LTSS because of chronic illness or disability. The remaining 44% of enrollees who use LTSS are 65 and older. In comparison, only 6% of Medicaid enrollees who do not use LTSS are ages 65 and older. Among people who use HCBS, 14% are under age 19, and 49% are ages 19-64, whereas over two-thirds of people who use institutional LTSS are ages 65 and older.

4. On average, Medicaid enrollees who use LTSS have Medicaid spending eight times higher than those who do not use LTSS.

In 2021, Medicaid per person spending was substantially higher for enrollees who used institutional care ($53,666), than for enrollees who used HCBS ($38,275), which was about 8-times greater than average Medicaid spending for enrollees who did not use any LTSS ($5,372) (Figure 4). Per-enrollee spending for those who don’t use any LTSS includes children who comprise 40% of Medicaid enrollees and tend to have much lower per-person spending. Children who use LTSS have spending ten times higher than children who don’t use LTSS ($30,933 versus $3,300). People who used Medicaid LTSS comprised 6% of Medicaid enrollment but 34% of federal and state Medicaid spending which includes the costs of LTSS, managed care premiums, and other services such as hospital care and prescription drugs. (It is not possible to say what share of Medicaid spending pays for LTSS because total spending includes payments to managed care plans, and the split of managed care payments by type of care is unknown). In 2021, Medicaid spending for the 5.7 million enrollees who used Medicaid LTSS, totaled nearly $234 billion. High per-person Medicaid spending among enrollees who use LTSS likely reflects the generally high cost of LTSS and more extensive health needs among such groups that lead to higher use of other health care services and drugs as well.

5. About 700,000 people are on waiting lists or interest lists for Medicaid HCBS, most of whom have intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Home- and community-based services (HCBS) waivers allow states to offer a wide range of benefits and to choose—and limit—the number of people who receive services. The only HCBS that states are required to cover is home health, but states may choose to cover personal care and other services such as private duty nursing through the Medicaid state plan. Benefits offered through a state plan are generally available to all Medicaid enrollees who need them. States may also use HCBS waivers to offer expanded personal care benefits or to provide additional services such as adult day care, supported employment, and non-medical transportation, though they can limit the number of people who receive these services. States’ ability to cap the number of people enrolled in HCBS waivers can result in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the number of waiver slots available. Waiting lists reflect the populations a state chooses to serve, the services it decides to provide, the resources it commits, and the availability of workers to provide services. A new rule on Medicaid access will require states to start reporting the number of people on certain types of Medicaid waivers known as “1915(c)” in 2027.

In 2023, a 50-state survey of Medicaid HCBS programs found that there were over 692,000 people on waiting lists or interest lists, and most people on waiting lists have intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD), particularly in states that do not screen for waiver eligibility before placing someone on a waiting list (Figure 5). People with I/DD comprise 88% of waiting lists in states that do not screen for waiver eligibility, compared with 51% in states that do determine waiver eligibility before placing someone on a waiting list. People with I/DD comprise almost three-quarters (72%) of the total waiver waiting list population. Seniors and adults with physical disabilities account for one-quarter (25%), while the remaining share (3%) includes children who are medically fragile or technology dependent, people with traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries, people with mental illness, and people with HIV/AIDS. People who are on HCBS waiting lists are generally not representative of the Medicaid population or the population that uses HCBS. Most people on waiting lists have I/DD, but KFF analysis shows that people with I/DD comprise fewer than half of the people served through 1915(c) waivers (the largest source of Medicaid HCBS spending).

6. In 2021, just 80,000 people filed claims for private long-term care insurance benefits.

In 2021, about 7.1 million people nationwide paid premiums for private long-term care insurance (LTCI), including standalone LTCI and also an array of products that pair life insurance or an annuity with some long-term care coverage (Figure 6). The age and other demographics of those people are unknown. In 2021, premiums for LTCI averaged $1,860 for the year. While those premiums may sound low relative to private health insurance premiums or to the costs of LTSS, LTCI is purchased before a person develops a need for LTSS and most people pay premiums for many years without using any benefits. That is one of the reasons that only around 80,000 people filed a claim for LTCI benefits in 2021. (Some people who had filed claims prior to 2021 continued to receive benefits in that year. In total, 1.5 million people have filed claims for LTCI benefits since companies started selling LTCI polices.) It is not uncommon for people to die without using benefits or to let their coverage lapse in response to rising premiums (or other factors) before they qualify for the benefits. Those are some of the motivating factors for products that mingle life insurance with LTCI, although in 2021, most of the people with LTCI still had standalone policies (6.3 million).

Unlike private health insurance, it is fairly uncommon for employers to offer and/or subsidize LTCI for their employees. A KFF survey showed that among firms offering health benefits in 2023, 25% offered LTCI and among those, only 39% contributed to the costs of coverage. There are a number of limitations of LTCI. Many policies don’t have inflation protection, limit eligibility for services, do not cover all expenses, and have lifetime limits. Some LTCI policies also don’t offer non-forfeiture benefits, meaning people who pay premiums for years may not get the premiums they have paid back if they let their policy lapse in the event of nonpayment (which may happen due to increased premiums after a rate increase). These unused premium payments can be especially considerable for people who sign up when relatively young. Insurers could also go out of business before coverage is needed.

7. Longstanding workforce shortages among LTSS providers were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic greatly exacerbated longstanding shortages of LTSS workers. Employment levels in all health care jobs dropped sharply at the start of the pandemic, but for most health care sectors, including hospitals, employment started to rebound as early as spring 2020. However, employment in the LTSS sectors continued to fall well into 2021 and for nursing facilities, into the beginning of 2022. Recent analysis on the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker shows that the number of workers in the LTSS sector (all nursing and residential care in Figure 7) was 4% lower in January 2024 than in February 2020. The reduction in workers is largest in the skilled nursing care settings, where the workforce remains 9% lower than in February 2020. Additionally, a 50-state survey of Medicaid HCBS programs found that all states reported shortages of HCBS workers, most frequently among direct support professionals, personal care attendants, nursing staff, and home health aides. Most states (43) also reported permanent closures of HCBS providers within the last year, with some closures reflecting provider shortages. These jobs are mentally and physically demanding, and direct care workers generally agree that the wages are low and do not reflect the demands of the work.

Beyond the formally paid workforce, there are also millions of family caregivers (most of whom are unpaid) who play an important role in filling care needs for older adults and people with disabilities. In 2021, about 38 million family caregivers provided, on average, 18 hours of care per week. Family caregivers deal with high levels of stress, often juggling work and school on top of their caregiving, as well as struggle with consequences of lost income including housing and food insecurity. Families may provide care out of love or a sense of responsibility, but many provide care because they can’t access paid care or are providing more care than they feel able to give based on their training and other life responsibilities.

8. Between 2015 and 2023, the average hours of care that nursing facility residents received decreased.

The adequacy of staffing in nursing homes has been a longstanding issue, and the high mortality rate in nursing facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and intensified the consequences of inadequate staffing levels. Between July 2015 and July 2023, the average hours of care that nursing facility residents received declined by 9%, from 4.13 hours to 3.77 hours (Figure 8). The decline occurred over the entire period but the number of hours of care per resident increased briefly in the year 2021. The relatively higher staffing hours in 2021 reflected the fact that the number of residents declined more quickly than the number of staff hours did between 2020 and 2021. Both the average number of deficiencies and the share of facilities with serious deficiencies increased over the same time period, which may in part reflect lower staffing levels.

On April 22, 2024, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released a highly-anticipated final rule that created new requirements for nurse staffing levels in nursing facilities. The final rule requires facilities to have at least 3.48 hours of nursing care per resident per day starting in 2026 for urban facilities and in 2027 for rural facilities. In later years (2027 for urban facilities and 2029 for rural facilities), 0.55 of those hours must be provided by a registered nurse and 2.45 hours from a nurse aide. The remaining 0.48 hours may be provided by any nurse staff type, including LPNs. The rule also requires facilities to have a registered nurse on staff 24 hours per day, 7 days per week; strengthens staffing assessment and enforcement strategies; creates new reporting requirements regarding Medicaid payments for institutional long-term services and supports (LTSS); and provides $75 million for training for nurse aides. KFF estimates that only 19% of nursing facilities would currently meet the three staffing hour minimums required in the final rule if it took effect immediately (3.48 hours overall, 0.55 RN hours, and 2.45 nurse aide hours).

9. States have taken steps to increase payment rates for home-based care, but workforce shortages persist.

In KFF’s survey of states’ HCBS programs, all responding states reported taking actions to address workforce shortages (Figure 9). The most common strategy reported was increasing payment rates to HCBS providers (48 states). However, even with the higher payment rates, among the states that were able to report time-based payment rates for personal care providers, most pay under $20 per hour. Some states implemented a permanent payment rate increase, but other states reported that payment rate increases for at least some of the workers were temporary. Other strategies reported include developing or expanding worker education and training programs (42 states) and offering incentive payments to recruit or retain workers (41 states). Less common strategies included establishing or raising the state minimum wage (20 states) and offering paid sick leave for workers (19 states). States also reported several other types of initiatives to strengthen the workforce, including creating platforms or support systems to connect job seekers with employers and positions, launching a social media campaign, and providing outreach to prospective employees. In another survey of states, most states reported increasing payment rates for nursing facilities and HCBS in 2023 and 2024.

Beyond state efforts, the Biden Administration has also taken steps to increase payment rates for the direct care workforce. A final rule on access to Medicaid services would require states to demonstrate that HCBS payment rates are adequate to ensure a sufficient direct care workforce and that at least 80% of total payments for specified HCBS are compensation to direct care workers. In a parallel vein, the final nursing facility staffing rule will require state Medicaid agencies to report the percent of Medicaid payments for institutional long-term services and supports (LTSS) that are spent on compensation for direct care workers and support staff.

10. An aging population will need more long-term services and supports.

A KFF interactive on the aging population shows that the percent of the United States population that is ages 65 and older is projected to grow from 17% in 2020 (56 million people) to nearly 25% in 2060 (95 million people) (Figure 10). During this period, the share of older adults who are in their 80s, 90s, and older will also grow. One in twenty of all people in the U.S. is projected to be 85 or older by 2060, a group that is likely to have the highest rates of LTSS needs and utilization as a quarter of them are frail. Advances in assistive and medical technology that allow people with disabilities to be more independent and to live longer, together with the aging of the baby boomers, will likely result in increased need for LTSS over the coming decades. An HHS report found that after age 65, over half of people would at some point need help with at least two activities of daily living, over half would use any type of paid LTSS, and over one-third would use some nursing home care. Expected rates of LTSS need and use are highest among people with lifetime earnings in the bottom income quintile, who have the fewest resources to pay for such care. Other research shows that among people ages 65 and older, those who are Black or Hispanic are much more likely to develop a moderate or severe LTSS than those who are White and have substantially lower financial resources to pay for LTSS. Racial and economic disparities among individuals experiencing LTSS needs may also have long-term intergenerational effects that can disproportionately affect people of color. The aging of the population raises difficult questions about how to address the challenges of coverage, affordability, financing, and workforce shortages to meet the needs of a growing population in need of LTSS.