In the living room of Randolph's apartment, a three-year-old boy glows as if showing off an electric tricycle. His father, Jack, smiles, but he has great concerns. Boston Hospital's boss said he would be let go if he could not secure a new immigration status.

“I don't know what I'm going to do because I have an apartment to pay, a car loan and I have a family in Haiti,” he said. “That's why I have a lot of responsibility.”

As a certified nursing assistant, he is one of many immigrants who have become dependent on the state's health care sector amidst a lack of staffing. But now the Trump administration has ended the program that allowed him to live and work in the country.

Jack's family is in the United States under temporary sheltered status. It is a long-standing humanitarian program that allows people facing dangerous situations in their home country to live and work here. As of March 2024, Massachusetts had around 28,000 TPS recipients.

“We rely so heavily on these migrant workers, and all of a sudden, most of them just evaporate.”

Dr. Asif Merchant

Wbur agreed to call Jacques by his nickname, as he fears being targeted by immigration police. He worked as a filmmaker in Haiti before coming to the US in 2021. He became a certified nursing assistant. This is a job that allows you to enter the industry after about two months of training.

Jack works in the artificial ward at a state hospital, taking vital signs and cleaning his bed frying pan. He earns $21 per hour, helps patients bathe and helps them move between their bed and wheelchair. It's a difficult, dirty job, Jack said, and many Americans don't want to do it.

Most of his fellow CNAs are “immigrants, two Jamaicans, one from Antigua, six or seven others from Haiti,” he said.

State officials say health facilities, which already struggle to hire sufficient workers, could face “significant disruptions” due to the end of TPS and other humanitarian programs, allowing thousands of migrants to enter the workforce.

The change depends on entry-level staff, which could be particularly in the long term health sector, experts say. The Massachusetts Senior Care Association, which represents around 400 nursing and rehabilitation facilities, estimates that 2,000 caregivers will be affected.

Crosshair TP

Temporary protected status is intended for those who are unable to return to their country due to political or environmental catastrophes. Over 1 million people from 15 countries have TPs. After the devastating earthquake in 2010, the Haitians were included.

Despite being designed as temporary, some winners have been in the United States for decades. Because both parties' presidents are expanding their programs so that they can stay. Others have only been here for a few months. Now it appears that the White House is ending one country at a time, including two largest groups, Haitians and Venezuelans.

The Washington, D.C. federal court case aims to stop the White House from terminating the TP for Haitians. The plaintiffs say the move is based on racism rather than improving Haiti's conditions.

However, the administration argued that the program “contradicts the national interests of the United States,” and Haitians must leave by February 3rd.

“Haiti isn't going well. If you take Haiti and move it to the US, it won't work here,” the controversial homeland security adviser said. “If we move the third world to the first world, we will eventually become the third world. That's not good for us, not good for those who want to live here in the future.”

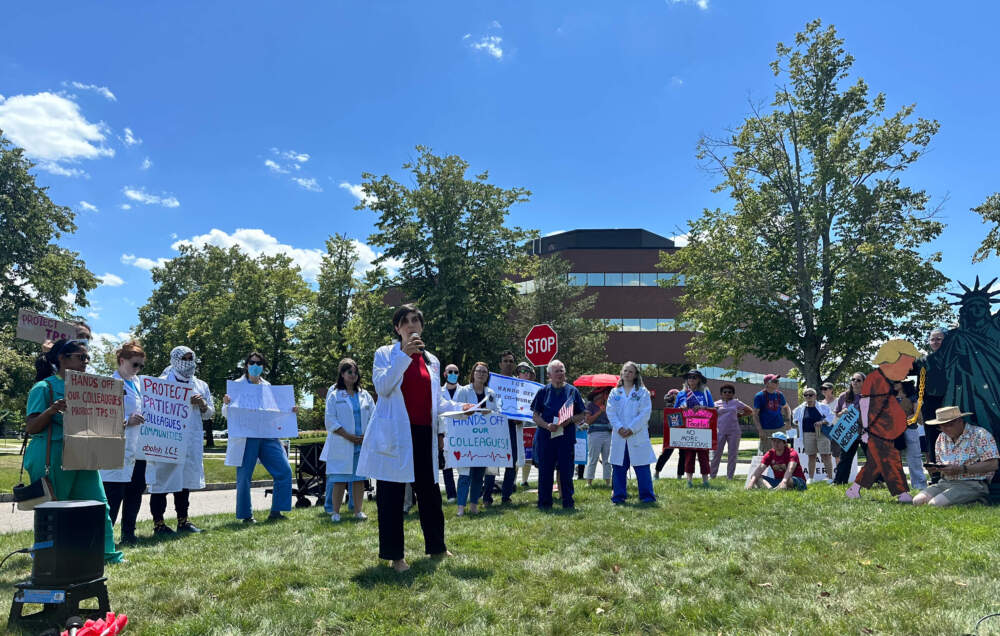

Even if the court ultimately enforces a February deadline, health care facilities in the Boston area have already seen workers leave, said Dr. Asif Merchant, medical director of five nursing homes in the area.

He said home health care and hospice will also be affected. In some cases, providers rely on immigration for the majority of their workforce. Beyond the CNA, the facility is also to lose kitchen staff and housekeepers, he said.

“We rely so heavily on these migrant workers,” the merchant said. “And all of a sudden, most of it just evaporates.”

The merchant said the facility he works supports losing 7% to 20% of his staff. It can lead to serving fewer patients and providing lower quality care. He said it's bad for patients, and that's bad for the provider's revenue.

“There are plenty of nursing homes already at very thin margins, which could lead to additional closures,” he said.

Recent research suggests that over a million non-citizens work in healthcare nationwide, with more than a third of today lacking legal status. Co-author Steffie Woolhandler, a doctor and health policy researcher at Hunter College in New York, said he has been teaching at Harvard Medical School for decades, saying that the crackdown on TPS would only increase the number of workers in countries with no legal status.

And she said it couldn't come at a bad time.

“Half of the country's nursing homes report that they had to stop acknowledging people because they didn't have the personnel to take care of them,” Woolhandler said. “And if we lose all these Haitian nursing aides, that number will go up.”

Woldhandler said it is unclear how many people will be affected in Massachusetts, but “anyone who works in healthcare in the area knows how important Haitians are.”

Economic impact

Under Biden, thousands of families have arrived from Haiti, arriving in Massachusetts from other countries. Governor Maurahealy's administration has made a significant investment in the new arrivals to help secure not only shelter beds but also work permits and vocational training.

Jeff Thiellman leads the International Institute for Refugee Resettlement, New England. He said many recent immigrants have entered the workforce with the help of the state. Through nonprofits like him, the state provided training in sectors with high demand for workers, including hospitality, construction and healthcare.

“A lot of the people who have trained over the past five to six years since the program was former healthcare workers,” he said. “They were nurses and in more cases, nurses in their home countries, so this is a way to get back to the scene.”

Currently, the end of TPS and related programs throws a wrench on the work.

“No individuals line up to replace Haitian communities and other immigrants who actually meet these jobs.”

Mark Williams, Professor BU

Thielman said one workforce preparation program managed by his group must close 600 of the 1,200 participants in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, as the humanitarian parole program in Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela has been eliminated, known as the CHNV.

“We can no longer work with these clients because they are not qualified to work,” Tielman said.

Another group that provides workforce training to new immigrants is Jewish occupational services. Kira Khazatsky, the group's chief executive, said 10% of clients who are highly employment-trained have lost their job permits.

“We have heard concerns and concerns from the business community about our ability to do business today and how we can grow both in the short and long term, not just in healthcare, but also in several other sectors,” Kazatsky wrote in an email.

Mark Williams, a finance professor at Boston University, is looking at what this means for a bigger economy. Before Trump's reelection, he predicted that state investment in recent arrivals would pay off in the long term as immigrants become taxpayers and children progress into more profitable careers.

Instead, Williams said a “seismic shock” is currently being prepared for the state.

“No individuals line up to replace Haitian communities and other immigrants who are actually filling these jobs,” he said. “And we already have a labor shortage in Massachusetts.”

Do you want to stay or go?

In their apartment in Randolph, Jack and his wife, Ivanne, cannot agree on what they will do when their status disappears in six months. They either bring their son back to Haiti's chaos or stay in the US, putting them at risk of deportation.

Jack is leaning towards staying. He said he could deliver food and work under the table, even if he lost his job in the hospital.

“I will take care of (my family) and do my best to pay my bill,” he said.

For Ivanne, there's no choice but to go back to Haiti.

“I want them to expand their TPS and allow them to work until the situation in their hometown is really improved,” she said in Creole, Haiti. “So we were able to go back home and return their country to them.”

Martha Bebinger of Wbur contributed to this report.