The balanced FCA model and the SAA index

To conduct our study, we used the balanced FCA (bFCA) model developed previously22 and used in other studies20,61,62. Conceptually, an FCA model computes the ratio of supply to demand within a catchment area centered at each supplier’s location, and then ‘floats’ these catchment areas over population centers to determine the allocation of the available resources to each of the demand sites. Catchment areas are delimited by specifying a maximum one-way travel time between the supplier’s location and the demand site. The bFCA model has an important advantage over the other types of FCA model as it corrects for issues of inflation of demand and service levels and takes competition among supply sites into account22. The bFCA model, as do all FCA models, produces an estimate of the spatial accessibility of a resource.

We used the bFCA model to estimate the SAA in Malawi, that is, to estimate, for each community in Malawi, their access to ART. The SAA reflects the geographic distribution of the HCFs that provide ART, the geographic distribution of the available supply of ART among HCFs, the geographic distribution of communities with people living with HIV, the mobility of the population (as specified by travel time to an HCF and mode of transportation) and the behavioral phenomenon of distance decay: the probability of using an HCF decreases as the time needed to travel to the HCF increases63,64. For a variety of reasons (for example, concern about being stigmatized), people living with HIV may choose not to use their nearest HCF; this behavior is referred to as bypass behavior and has been observed in SSA65,66,67. The bFCA model allows bypass behavior by letting people living with HIV use any of the HCFs that lie within their community’s catchment area.

The bFCA model is specified by five equations. For our application of the bFCA model, we specify communities as demand sites and HCFs as supply sites. The model includes i communities (i ∈ {1,…, N}) and j HCFs (j ∈ {1,…, J}). Equation (1) calculates the demand for ART at each HCF in the country; demand is specified in terms of the number of people living with HIV. The demand at each HCF depends upon how many communities are in its catchment area, how many people living with HIV each of these communities contain, the travel time from the HCF to each community, the mode of transportation used and the behavioral phenomenon of distance decay. It is defined by:

$${D}_{j}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{{{i}}={{1}}}^{{{N}}}{{{P}}}_{{{i}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{i}}}$$

(1)

where the demand (Dj) at HCF j is the sum of the number of people living with HIV (Pi) in community i, weighted by the probability (\({W}_{{ij}}^{\,i}\)) that people living with HIV from community i use HCF j. \({W}_{{ij}}^{\,i}\) is a standardized impedance weight. People living with HIV from community i can use HCF j if community i lies within the catchment area of HCF j.

Impedance weights (Wij) provide a measure of the difficulty of moving from community i to HCF j given a specified mode of transportation. They are estimated by using a function f(∙) that depends on the travel time tij between community i and HCF j, using a specified mode of transportation. f(∙) is modeled with a decreasing function to represent the behavioral phenomenon of distance decay63,64. HCFs cannot be used by a community if they are outside the community’s catchment area. By evaluating f(∙) for all travel times tij, impedance weights \({W}_{{ij}}=f\left({t}_{{ij}}\right)\) are obtained. The impedance weights are then standardized:

$${{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{i}}}={{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}/\mathop{\sum }\limits_{{{j}}}^{{{J}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}\;{\rm{such}}\; {\rm{that}}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{{{j}}}^{{{J}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{i}}}={{1}}$$

(2)

Equation 3 calculates the level of service (Lj) at each HCF j in the country. The level of service at an HCF is a measure of the localized supply-to-demand ratio in the catchment area of that HCF. It is calculated by dividing the supply at the HCF by the localized demand at that HCF:

$${{{L}}}_{{{j}}}=\frac{{{{S}}}_{{{j}}}}{{{{D}}}_{{{j}}}}=\frac{{{{S}}}_{{{j}}}}{{\sum }_{{{i}}={\bf{1}}}^{{{N}}}{{{P}}}_{{{i}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{{{i}}}}$$

(3)

The supply Sj of each HCF j is defined to be the maximum quarterly number of people living with HIV treated at HCF j during the year.

Equation (4) calculates the SAA index for community i (SAAi). SAAi is the weighted sum of the level of service at all of the HCFs that are contained within the catchment area of community i:

$${{\rm{SAA}}}_{{{i}}}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{{{j}}={{1}}}^{{{J}}}{{{L}}}_{{{j}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{j}}}$$

(4)

Here the standardized impedance weight (\({W}_{{ij}}^{\,j}\)) is the probability that HCF j can be used by people living with HIV in community i; it is calculated as follows:

$${{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{j}}}={{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}/\mathop{\sum }\limits_{{{i}}}^{{{N}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}\;{\rm{such}}\;{\rm{that}}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{{{i}}}^{{{N}}}{{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{j}}}={{1}}$$

(5)

The standardized impedance weights produce the ‘balance’ in the model by preventing inflated demand and service levels, which occur in other types of FCA models22. For example, without these weights, there could be multiple communities with high probabilities of using the same HCF at levels that are not commensurate with the ART supply available at that HCF.

The spatial potential accessibility ratio

The spatial potential accessibility ratio (SPAR) is a measure of a community’s accessibility to the available supply of healthcare resources relative to the national average68. For example, if a community has a SPAR of 0.5, then its accessibility to ART is 50% lower than average. A good score is a value of SPAR > 1; the higher the value, the better the accessibility to ART relative to the average. A bad score is a value of SPAR < 1; the lower the value, the worse the accessibility relative to the national average.

Parameterization

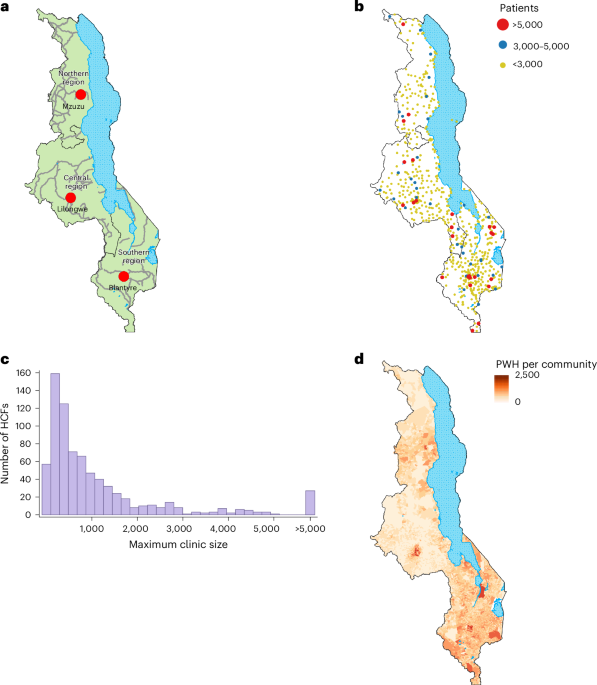

To parameterize the model, we needed to know, for 2020, (1) the geographic location of every HCF that provided ART, (2) the supply of ART at each HCF, (3) the geographic location of every community in Malawi, (4) the number of people living with HIV in each community (demand) and (5) the standardized impedance weights. We programmed the model in R (v.4.1.2)69.

The geographic location of every HCF that provided ART

Each of the 758 HCFs that provided ART in 2020 was geolocated at the geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) obtained from the master list provided by Malawi’s MoH.

The supply of ART at each HCF

Malawi’s government-funded national healthcare system is free for all Malawians at the point of delivery. The supply of ART (Sj) at each HCF j was estimated from 2020 data provided by Malawi’s MoH. Malawi used a centralized ART distribution system that was based on push dynamics: (1) all HCFs that provided ART were consulted quarterly by the MoH as to how much ART they needed for the next 3 months, (2) they were allocated the amount they requested and (3) they distributed all of the ART that they received. Supply data were validated each quarter. Malawi uses multi-month scripting for ART: prescriptions are typically for 3 months. The distribution system ensured that all people living with HIV who requested ART in 2020 received treatment; there were no stock outs, and HCFs were not underutilized (that is, they did not have a supply of ART that was not utilized). Based on this distribution system, we defined the total supply of ART that was provided in 2020 as the maximum number of people living with HIV that were treated in 2020. We estimated the supply at each HCF by calculating the maximum quarterly number of people living with HIV (aged 15 or older) that were treated, at that specific HCF, in any one of the four quarters in 2020.

The geographic location of every community in Malawi

Each community was geolocated at the population-weighted centroid of their enumeration area70. The population was specified in terms of the number of people living with HIV in the community.

The number of people living with HIV in each community (demand)

We estimated the demand for ART in each community in terms of the total number of people living with HIV they contained. To estimate these numbers, we first constructed an HIV prevalence map for people living with HIV aged 15 or older (Extended Data Fig. 3a; maps of the corresponding 95% confidence intervals and standard errors are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3b–d). The prevalence map was based on HIV-testing data collected in MPHIA223. The MPHIA2 survey collected blood samples from a representative sample of the population of Malawi in 2020–202111. These data were collected between January 2020 and April 2021; the majority were collected in 2020. The survey used a two-stage cluster sampling design. All individuals were nested within georeferenced survey clusters; the clusters were geomasked to ensure anonymization56. The individual-level data on HIV testing (n = 22,662) were aggregated at the cluster level.

We created the HIV prevalence map by using EBK55 to spatially interpolate the cluster-level HIV prevalence estimates calculated from the MPHIA2 data. EBK is a geostatistical technique for spatial interpolation; it uses a function (in our case, a K-Bessel function) to model the empirical semivariogram. The semivariogram reflects the degree of spatial correlation in the data. EBK accounts for the error in estimating the semivariogram by deriving a distribution of empirical semivariograms at each location. A geographic visualization of the distribution of semivariograms at four different locations is shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. We used cross-validation to assess how well the EBK model was able to predict values at locations where HIV prevalence data had not been collected. Cross-validation metrics are shown in Supplementary Table 9.

After constructing the HIV prevalence map, we combined it (using raster multiplication) with the gridded raster dataset (for 15 years and older) of the 2020 WorldPop data57 for Malawi; this produced a density of infection (DoI) map (Extended Data Fig. 5). WorldPop data are gridded data of population density at a resolution of 100 m by 100 m; data are updated annually to reflect UNAIDS-predicted urban–rural growth rates. We used the top-down constrained version of the 2020 WorldPop dataset. The DoI map was constructed at a spatial resolution of 100 m by 100 m. We then used ArcGIS to partition the DoI map into the 9,208 communities in Malawi and estimated the number of people living with HIV in each community. The total number of people living with HIV in community i is Pi.

The standardized impedance weights

To calculate the standardized impedance weights, we first calculated an origin–destination (OD) matrix of travel times. In the OD matrix, the columns represent HCFs and the rows represent communities; the coefficients of the matrix specify the travel time tij between every community i and every HCF j, based on a specified mode of transportation. As in all FCA models, all travel times begin from the population-weighted centroid of the community’s enumeration area. To calculate travel times, we used an impedance map24. This map is essentially a three-dimensional representation of Malawi; it includes data on topography71, land cover72, rivers and other water bodies72, and road networks73. The map provides estimates of the time needed for an average individual to traverse each square kilometer of Malawi, using a specified mode of transportation. We calculated this map using AccessMod (v.5)37, geospatial data files70,71,72,73 and travel speeds for several modes of transportation (Supplementary Table 10). Previous studies have used Google Maps Platform Application Programming Interfaces to estimate travel times to HCFs in Africa74,75. We used the platform to estimate the average travel time needed to travel 1 km in Malawi (for each type of road in our study; Supplementary Table 10); we then calculated the reciprocal of this value to obtain the average travel speed (in kilometers per hour). Using these travel speeds and the impedance map, we calculated the travel times between all HCFs and all communities. As there are 758 HCFs and 9,208 communities in Malawi, there are ~7 million coefficients in the OD matrix.

We then used the OD matrix and a distance decay function f(∙) to calculate the impedance matrix. f(∙) was estimated by using a data-based methodology that was designed to estimate a distance decay function for an FCA model76. The distance decay function fitted to the data is shown in Extended Data Fig. 6. Using this function enabled us to operationalize the phenomenon of distance decay: the further individuals have to travel to reach an HCF, the less likely they are to visit the HCF; this phenomenon has frequently been found to occur in SSA63,64. We calculated the coefficients for the impedance matrix by evaluating f(∙) for all travel times in the OD matrix (that is, we calculated f(tij)). Notably, the majority of the coefficients were zero, as people living with HIV in any given community are not able to reach the majority of HCFs in the country within their specified maximum one-way travel time. The impedance matrix was then row standardized and column standardized, as in equations (2) and (5), respectively, to ensure that the population was allocated proportionally to the HCFs. The resulting matrices contain the standarized impedance weights \({{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{{{i}}}\) and \({{{W}}}_{{{ij}}}^{\,{{j}}}\) for the model.

We calculated standardized impedance weights based on each mode of transportation: walking only or a combination of motorized transportation, bicycling and walking.

Spatial sensitivity analysis

To conduct the spatial sensitivity analysis, we varied catchment size; the size was defined by setting catchment boundaries. Boundaries were set by constructing an impedance map of Malawi24, specifying a maximum one-way travel time between supply sites (HCFs) and demand sites (communities), and stipulating a mode of transportation.

We varied two factors that delimit catchment boundaries: the maximum time that people living with HIV spend traveling (one way) to HCFs to receive their medications and the type of transportation that they use to reach HCFs. The 2020–2021 MPHIA2 data indicate that 44% of people living with HIV on ART spent less than 1 h traveling to an HCF, 37% spent 1–2 h and 19% spent more than 2 h (ref. 23). We used three values to specify the maximum one-way travel time: 1 h, 2 h or 3 h. The MPHIA2 survey also collected data on the ownership of different types of transportation. Only 2% of households owned cars or trucks, 4% owned motorbikes or scooters, and 34% owned bicycles23. Therefore, we modeled two modes of transportation: the slowest possible (only walking) and the fastest possible. The fastest possible mode was based on using a combination of three types of transportation: motorized transportation, bicycling and walking. The type of transportation used depends upon the type of road or track that is traveled on (Supplementary Table 10). By crossing the two factors (the maximum one-way travel time and the mode of transportation), we examined six catchment sizes in the spatial sensitivity analysis. The longer the maximum travel time and/or the faster the mode of transportation, the larger the catchment. The smallest catchment size was based on walking one way for a maximum of 1 h. The largest catchment size was based on using a combination of the three types of transportation and traveling one way for a maximum of 3 h.

Varying travel speeds

We conducted an analysis to investigate the impact of varying travel speeds on the geographic accessibility of HCFs. Following published methods41,77, we examined slower and faster travel speeds relative to the baseline travel speeds that we used in our spatial sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table 10): specifically ±20% of the baseline travel speeds. We considered two modes of transportation: walking or using a combination of motorized transportation, bicycling and walking, with a maximum one-way travel time of 2 h.

Model verification

In all bFCA models, the sum of the level of service (equation (3)) for all of the HCFs should equal the sum of the SAA index (equation (4)) for all of the communities. We verified the bFCA model that we used in our analysis by checking, for all six catchment sizes in the spatial sensitivity analysis, that this relationship held.

Calculating Lorenz curves and Gini coefficients

We conducted a country-level equity evaluation of access to ART in Malawi in 2020 by using econometrics to calculate and visualize an overall summary measure of the degree of inequity in access. The Lorenz curve26 and the Gini coefficient27 are metrics developed over a century ago to quantify economic inequities at the national level. If the income distribution in a population is perfectly equal, the Lorenz curve is a diagonal line; the further the curve is from the diagonal, the greater the inequity. The Gini coefficient measures the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of absolute equality, and is expressed as a percentage of the maximum area under the line. Thus, a Gini coefficient of zero represents perfect equity, while a value of one implies complete inequity. Both the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient have previously been used to measure health inequities78,79.

First, we computed a Gini coefficient based on each of the six catchment sizes explored in the spatial sensitivity analysis. We then constructed the six corresponding Lorenz curves. Lorenz curves were constructed by computing the cumulative distribution function of the SAA index.

Geostatistical clustering analysis

To determine whether there was significant spatial clustering in communities based on their SAA index, we calculated the Global Moran’s Index28. This index measures the strength of the spatial autocorrelation between neighboring communities and varies from −1 to +1; negative values signify dispersion and positive values signify clustering of communities with similar values of the SAA index. For the SAA indices generated, based on the six catchment sizes explored in the spatial sensitivity analysis, we calculated the Global Moran’s Index. We then calculated the LISA statistic29 and plotted country-level LISA cluster maps.

Spatial uncertainty analysis

To determine the robustness of our results in identifying the existence and geographic location of HIV treatment deserts, we conducted a spatial uncertainty analysis. To conduct this analysis, we determined, for each of the six catchment sizes that were explored in the spatial sensitivity analysis, which communities occurred in deserts and then plotted the results in the form of a heat map of Malawi. The heat map shows the number of times a community is found in an HIV treatment desert: a value of 0 signifies that the community living in that specific location is never found in a treatment desert and a value of 6 signifies that the community living in that specific location is always found (that is, for every catchment size) in a treatment desert.

Calculating the numbers treated per 100 people living with HIV

We calculated, using data from the MoH, the number of people living with HIV (per 100 people living with HIV) who were treated with ART at HCFs inside deserts by (1) summing the number of people living with HIV who were treated with ART at every HCF that was in a desert, (2) summing the number of people living with HIV in every community that was in a desert and (3) dividing (1) by (2) and multiplying by a hundred. We made the same calculation for the number of people living with HIV (per 100 people living with HIV) who were treated with ART at HCFs outside deserts.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in R (v.4.1.2)69 and GeoDa (v.1.22.0.4)80. Summary numbers and statistics are presented as means unless otherwise indicated. Two-sample t-tests were used to compare the mean SAA index inside and outside deserts; significance was assessed at α = 0.05. The LISA cluster maps were created in GeoDa; clusters and spatial outliers were assessed using two-tailed tests at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Ethics and inclusion statement

This project was initiated by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, in collaboration with researchers and medical doctors from Partners in Health in Malawi, and the Ministry of Health of the Government of Malawi. As such, this paper includes authors from many backgrounds throughout the international scientific community. Roles and responsibilities were agreed upon before the research was conducted. From the early stages of the project, all team members collaborated on data ownership and study design. Our study is focused on Malawi; therefore, in-country experts were team members. These team members played a critical role in providing detailed knowledge of Malawi’s medical system with a focus on HIV treatment. All team members are co-authors of this paper. We have cited local and regional research that is relevant to our study. As our study has focused only on modeling, capacity building has not been discussed.

This study involves secondary analysis of data that were collected from previous studies. The MPHIA2 data that we have used are publicly available; during its original collection, the PHIA study protocols were reviewed and approved by in-country ethics and regulatory bodies. The Malawi ART supply data were provided to us in the form of aggregated, de-identified HCF-level data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.